Predicting the future is hard

Predicting the future is hard.

|

Whilst you can make best-case predictions of how technology might change, and what the future may hold; there are always unforeseen advances that make step changes. Extrapolation ceases to be accurate over sharp edges. |

|

Yes, visionaries can be people who use imagination to predict things outside the world we live in, but they are either eerily prophetic or just plain wrong. Where are our invisibility cloaks, faster than light engines, and anti-gravity motors? Conversely, just a couple of decades ago the concept of smartphones, GPS, quantum computing, the internet, and staggering levels of raw computing power, which seem so natural to us now, would seem like magic before discovery. In the words of Arthur C Clarke, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” |

|

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Economists describe the technology associated with these step changes as disruptive technology.

Science Fiction usually gets it wrong too

|

Look at science fiction films and books (written, arguable, by people who are most qualified to predict the future); they typically miss these step changes. Even science fiction films made just a dozen years ago already look “dated” because they use quaint technology that we’ve already long since bypassed. |

Common anachronisms include the total missing of flat panel display technology. In all but the most recent productions, depictions of space ships show them all still using heavy glass CRT TV screens (classically fixed pitch 80 column characters, often with green phosphor, using screens with noticeable curvature. The advanced computers sometimes use ASCII art! and always the refresh rate is pretty poor and flickering).

|

If we are to believe movies, yes, we’ll have video calling in the future, but most missed the concept of smart phones. Everyone goes to a video phone booth to make a call (again on a CRT screen), rather than taking a device out of their pocket to make the call (and then typically pay through the insertion of a physical token/coin/card, not through some concept of an online account). When these movies were made, nobody had thought of the concept of smartphones, facetime, or wireless data plans! |

|

Computer rooms in older movies are depicted as rows of boxes with spinning spools of magnetic tape and blinking lights (OK, they got the blinking lights part right; it’s not computer unless it has blinking lights!) Printers use ribbons, dot matrix print heads, and sprocket feeds. Fax machines are still common. |

In Star Trek, why does Commander Data use a physical keyboard to interface with ships’ computers and not simply use Bluetooth? In the first series, how come the tri-corder does everything but communication, and they have to carry a second device (the compact flip phone) that just allows voice chat (and no texting, and no data). Also, why do they need to visit the transporter room to get from place to place? If you can move matter from one spot to the other, why not simply go point-point (if you need to, sure, going intermediately through a teleport hub, but this could be sealed room; why have to walk down there?).

|

We don’t having flying cars, or hover boards, and using CDs to transport data is passé. Some things that are still on the fence: In Blade Runner, people are still smoking cigarettes (a lot it seems), and are reading traditional print newspapers (ostensibly to hide behind). |

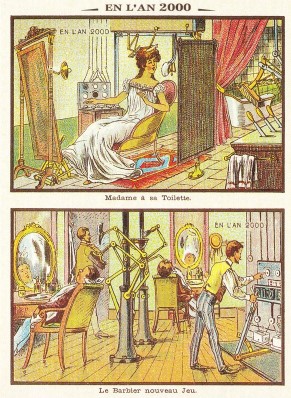

Postcards from the Future

Image: Ed Fries Image: Ed Fries |

There's a great presentation by Ed Fries, entitled Postcard from the future. He examines a collection of postcards, created 100+ years ago, with predictions and depictions of life in the future. If we were to believe the Victorian view of the future, we’d all be living in floating cities in the clouds (or under the sea). Transportation would be in flying cars, powered by propellers (no concept of jet engines), and with no concern about aerodynamic smoothness (the challenges of speed and compressibility of air had yet to be encountered), nor how to breathe in space! The Victorian view is that we would have robots as such, but these were depicted as controlled automaton. The predictions didn’t appreciate the concept of AI or computer control, so all drawings show complicated remote control mechanisms; still with human operators. Compounding this is the missed concept of radio. All the automaton devices are shown connect to their controller with complex mechanic linkages or wires. The whole concept of wireless communication was missed. Oh, and we don’t yet have colonies on the moon. The Victorians thought that we would. As comical as these might appear, just imagine what people 100 years from now will think about the movies, TV shows, books, and podcasts that are written today! |

Steampunk

Image: PaulR1800

Image: PaulR1800 |

The Steampunk genre of science fiction embraces these anachronisms, and celebrates them. This culture thrives in the universe of imagining what would happen with the extrapolation of Victorian steam age technology and clockwork. It’s a mash up of HG Wells, Jules Verne, Victorian England, and the Wild, wild, west of pioneering USA. There’s lots of brass, pipes, knobs, dials, cogs and spigots. |

Step changes in technology can have catastrophic effects on businesses

|

Businesses that fail to pivot quickly to disruptive changes in technology will fail. Once upon time, Kodak had the lion’s share of the photography market with over 90% of film sales in the USA being theirs!. George Eastmans’s goal was “to make the camera as convenient as the pencil.” (Which, ironically, smartphones are today). At peak, the Kodak Company was valued to $31B, employed over 145,000 people and was the fifth most recognized brand on the entire planet. It failed to pivot fast enough to the technology change of moving to digital from print film medium. Just a dozen years later, it filed for bankruptcy. Founded in 1880, it ended in 2012. |

There are plenty of other examples of technology changes disrupting businesses: The bound and print encyclopaedia business, classified adverts in newspapers, long-distance propeller driven passenger aircraft in the jet age, video rental chains, first generation mobile phones (and later Blackberries), high street bookchains, catalog companies …

There’s a quote that’s attributed to Henry Ford, the father of the first mass produced car, (it’s questionable if it’s really from him, but it's a nice quote). The meme goes that when he asked people what they wanted, they thought inside the box, not outside.

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

To stay alive in today's business world, it's not enough to religiously iterate and improve your core product; that's simply an essential costs of doing business. You have to be constantly on the lookout for the next step change in your arena, and be sure to adapt, nimbly, before someone else jumps in and steals your customers.

Moravec's Paradox

All of this setup lands us at the topic I wanted to discuss: Moravec’s Paradox.

What this essentially states is that, paradoxically, things that are really easy for humans to do, are really, really challenging for computers, and the inverse; many things that are hard or impossible for humans to do can be performed, at lightning speed by computers.

I think this contributes to why science fiction still gets things wildly wrong.

The paradox is named after Hans Moravec, from Carnegie Mellon University, in the 1980s.

There are certain things even a small child can trivially do: Balance, recognizes faces, distinguish between what is a cat and a dog, untangle a ball of string, wash plates, fold a shirt, ride a bike, plant a flower, crack an egg without making (too much) mess …

All of these easy-for-human tasks are either still not reliably performable by computers/robots, or those that are require enormous computation resources to achieve. Many of these skills are achievable by humans unconsciously.

|

On the flip side, computers can multiply hundreds of millions of numbers a second (something even a stadium full of human savants could not even get near), or sort things, or find patterns, or check billions of combinations of outcomes. There are some things that computers are just infeasibly brilliant at (typically things that involve a lot of math and calculations), that humans can’t even begin to get close to. |

|

|

What this means is that we still don’t have robots the way that classic Sci-Fi depicts them. For the last 50 years, artificial intelligence, and dexterous robots have been “around the corner”, but each decade goes by, and despite things like Moore’s Law helping double the computing horsepower we have on-tap every 12-18 months, we’re still a long way away from getting them to do tasks that even our children can do. |

We now have super computers that measure their processing power in tens of petaflops (tens of quadrillions of calculations per second), but we still can’t build a robot to that can untangle a string of Xmas tree lights! (don’t you just hate it when they get knotted in a box?)

Put another way; high-level reasoning requires relatively little computation power, but tasks requiring low-level functions, such as sensor/motor skills require enormous computational resources.

Moravec, and others, go on to speculate that, because of this, robots and automation will not lead to fewer jobs, but just shift the tasks that humans do. Not all jobs are feasible to automate.

To quote Kallum Pickering, an analyst from Berenberg “Producers will only automate if doing so is profitable. For profit to occur, producers need a market to sell to in the first place. Keeping this in mind helps to highlight the critical flaw of the argument: if robots replaced all workers, thereby creating mass unemployment, to whom would the producers sell? Because demand is infinite whereas supply is scarce, the displaced workers always have the opportunity to find fresh employment to produce something that satisfies demand elsewhere.”

Speculation is that the jobs that won't be automated are the ones that are easy for humans to do (the less well paid jobs), leaching out the middle class resulting in a bifurcated society to a small number of very rich people employing armies of poor people whilst the robots perform all the tasks in the middle. We shall see …

Back to the movies

More subtly, Moravec’s Paradox shows how, again, science fiction movies apply technology in mismatched complexities. They don’t apply the disconnect about what is hard and what is easy.

In the Terminator series, for instance, we have killer robots that are sophisticated enough to walk, balance, dress in clothes, drive cars, and ride bikes. These must be fantastically phenomenal devices to be this dexterous under computer control. Why then, are they such bad shots? If they were this advanced, they would be able to single shot any target they wanted! The entire movies are based on them chasing and failing, multiples times, to kill their targets*. The Moravec-hard tasks of balancing/walking are all taken care of, so the ballistics calculations of where the point the gun would be trivial to the robots.

*Don’t get me wrong, I love the movies, I’m just pointing up the technical inconsistencies.

Ending with humour

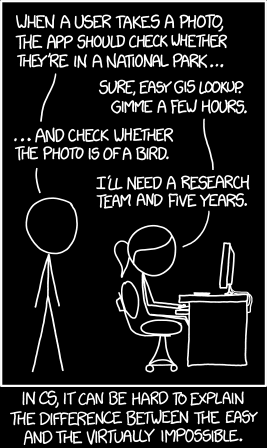

There's a great XKCD comic about Moravec's Paradox:

|

"In the 60s, Marvin Minsky assigned a couple of undergrads to spend the summer programming a computer to use a camera to identify objects in a scene. He figured they'd have the problem solved by the end of the summer. Half a century later, we're still working on it." |

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.