d20 stopping puzzle

|

Another die rolling probability puzzle game this week. This puzzle involves a single d20 (a twenty sided die); something that anyone who has played Dungeons and Dragons will be intimately familiar with. Typically they are made in the shape of an icosahedron, the most complex of the platonic solids. The puzzles goes like this: We play a game. You roll the die, and can elect to bank, or roll again. If you bank, you walk away with the dollar amount shown on the die, and the game ends. If you elect to re-roll, it costs you $1 for each new roll. You can re-roll as often as you like. (Your first roll is free). What is your Expected Return? |

|

What is the optimal strategy to maximize your winnings? If you follow this strategy, what is your expected return? If you stop early, you’ll not have spent much money on re-rolling, so your potential profit might be higher. If you keep rolling and rolling, hoping for a better score, are you leaching away your potential profit? If you go negative, do you ‘keep the faith’ and keep investing in more rolls to break even, cut your losses and stop, or carry on waiting for a big score to make it right? |

|

Initial Thoughts

Does the optimal strategy involve a dyanmic stopping strategy (one in which the decision is somehow based on our current balance)?

|

No, that can't be the case: The die has no memory of rolls already made and the current value of your balance has no bearing on the expected outcome yet to come. Any money spent (invested) in getting to this stage is a sunk cost, and is water under the bridge. At every roll, we need to make the call: "Should I make the next roll?", and from the above arguments you can see that this decission will be same if this is the first roll, the fifth roll, or the tenth roll. |

|

There is no way to win money back already spent, and there is no limit to the number of rolls you can make. Once you decide to pay the $1 to roll again, the characteristics of what happens are the same as the previous roll. The difficulty is that the decission to stop is based on if we roll above the future expected value, but this, in-turn, is based on the expected value. |

|

Should I stay or should I go?

There's a decission that needs to be on each roll. Should I take what I have, or pay the tax and roll again? (Paying the tax is same as saying we get one less dollar than the expected value of the next roll).

It's pretty clear that if we rolled a natural 20 at any time, we'd instantly stop; We're never going to get better. It's not a stretch to see that, if we rolled a 19, we'd also stop; The only number that could beat a 19 is a 20, and we'd have to pay an additional $1 just for the privelage of rolling to see about getting it. Even if we did roll a 20 (a small chance), we'd net out with no gain, so why bother? For 18, it's less clear; we have a one chance of breaking evening, one chance of improving, and lots of chances of losing more, if we rolled again.

Let's imagine there is some threshold T, yet to be determined, above which we'd bank and stop. Below which we'd carry on rolling.

This threshold would be based on the expected return. If we stop, we take the current count, if we carry on, we take the expected value of the roll yet to come (which is exactly one dollar less than the current expected value).

Here comes the math …

Amongst my friends and colleagues (with whom I often test my blog questions in advance), this question certainly caused a good amount of discussion, and there were many schools of thought. Thankfully, it's one of those problems that is very easy to test a proposed strategy on. With a few lines of code you can implement your chosen strategy and test it out Monte-Carlo style with a few million random rolls of die. This simple strategy provided evidence that some colleagues' suggestions were sub-optimal without needing to find the incorrect assumptions in their respective models.

Using the threshold T, the probability that we will roll greater than this value is (20-T)/20, and the expected winning (this is just the average) if we take this path is (T+21)/2.

Using the threshold T, the probability that we will roll less than or equal to this value is T/20. The amount that could be obtained is the 'expected value less one dollar'; we multiply these to get the expected return if we follow this path. We add this to the first term (OR) to get our equation.

We're still trying to find the expected value which is on both sides of the equation. A little bit of simplification:

Now we collect terms of E on one side.

Now that we have an equation for E in terms T, we can differntiate to find turning points. If we then set this to zero, we can find out the value this occurs. (Differentiating a second time results in a negative value confirming our turning point is a maximum).

This results in a quadratic we can solve to give a value for T (rejecting the impossible radical answer).

We need a discrete value for T (dice are quantized to give integer answers) so T=14, and this is the threshold about which we need to be greateer than. Let's work out the expected value if the exceed threshold is 14.

E[T=14] = 151/6 (max)

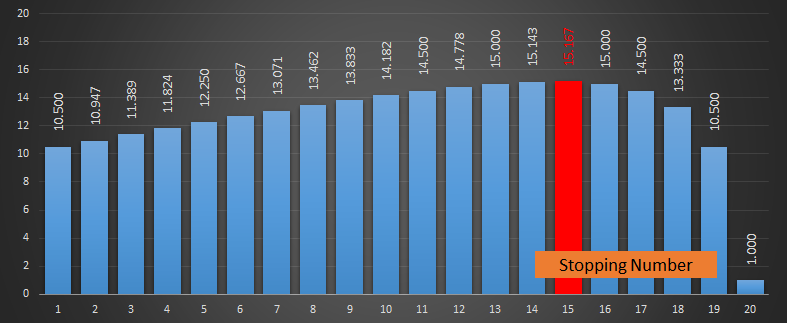

So the optimal strategy is to stop and cash out only if the die shows 15 or higher, else keep spending $1 to roll again and again, leading to expected winning of 151/6. Below is a graph of the expected returns y-axis, plotted against the fixed stopping value value on the x-axis.

In a piece of great relief, I generated the same graph using both the equation for E and the running a few million simulations using Monte-Carlo and obtained the same values (within the tolerances of the random number generator).

Answer

The optimal strategy to this game is to continue rolling until you first obtain a score of 15 or above. If you stop at this time, your expected earnings are $15.67

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.