Efficient Guttering

What’s the most efficient shape to make a gutter?

If we have a flat sheet of thin metal, and we want turn it into a gutter (or trough), what’s the most efficient geometry? For most efficient, I’m asking which shape of gutter will hold the most water?

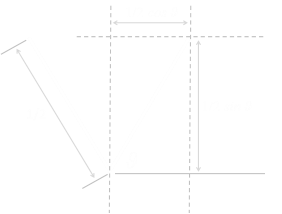

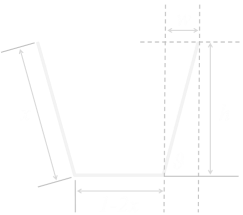

Single Bend

|

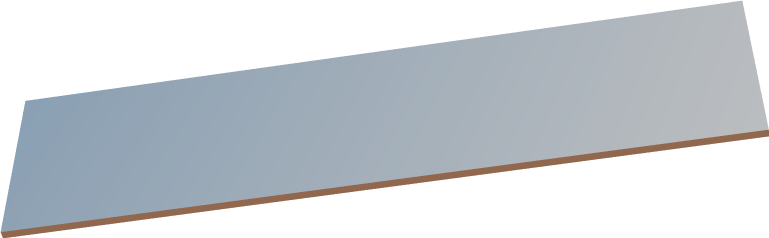

If we can only make one bend, then we can fold the sheet down the middle to make a ‘V’ gutter (down the middle for symmetry). I hope it’s obvious that it has to be down the middle — if the arms of the valley were at different heights, the taller excess of the arm above the water level would be wasted metal. |

|

What’s not as obvious is the angle we should bend the metal. Is it more optimal to have a tall, narrow “V” or a broad, shallow “V”? Let’s use some calculus to find out. (If we were not restricted to straight lines, then a semi-circular trough would maximize the capacity). |

|

|

We’ll look at a cross-section through the gutter, and normalize the width of the source sheet to be of width one unit. The area of this cross section is a representation of the amount of water the gutter can hold; we’ll call this area A. Our goal is to maximize A. We’ll define the angle the gutter makes to the horizontal as θ, and we can see that each arm of the gutter is length ½ units. |

The area A is easy to calculate. It’s two of the triangles.

Differentiating this and setting to zero allows the turning points to determined:

(The second differential is negative confirming the turning point is a maximum).

|

The optimal “V” gutter shape can be obtained by bending the sheet to make an angle of 45° to the horizontal – this results in a right angle in the middle. If you can only make one bend, make it 90° |

Double Bend

|

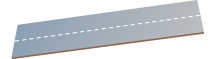

What about two bends? If we are able to make two bends, what is our optimal strategy? Is it optimal to make a square “U” shaped gutter with the perpendicular sides? If so, should it be square in section, or rectangular? Or, should we bend the sides out? If so, what angles, and what percentage of the metal should be dedicated to the base, and what to the wings? Again, calculus comes to the rescue. We need a few more variables to define a generic trough. Again, we're applying the priniciple of symmetry. As before, we'll normalize with width of the sheet to be one unit, and define length of one of the winged sides to be x. |

Because the width of the sheet is one unit, this means the base of the through is 1-2x.

Again, we'll use θ for the angle from the horizontal, and define h to be the height of the gutter, and w to be the overhang.

The area of the gutter cross-section is the area of the trapezium, which is the area of the rectangle section in the middle plus the two triangles.

From geometry:

Substituting in:

We wish to maximize A and there are two variables we can adjust, x and θ, for each we will differentiate A with respect to these variables and set the answer to zero to determine the turning point. First with respect to x:

Next we wish to differentiate with respect to θ:

Substituting back in cos θ:

Substituting this back into allows us to determine the angle:

|

The optimal gutter with two bends has sides with angle 60° and the bottom and sides are of equal length. |

Nature

|

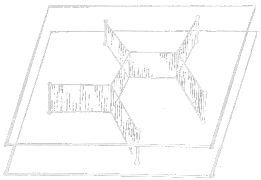

If you look closely, you'll see this gutter shape is half a hexagon. You'll see this shape everywhere in nature. Bees make their honeycombs using these angles. When mud dries and cracks, it forms hexagonal patterns. When magma and molten rocks cool, they form hexagonal columns. |

Here's Giant's Causeway in the UK. These are bassalt columns (sometimes called prisms by geologists).

Image: Travis S

Image: Travis S

Why?

As hinted at by our gutter calculus, using straight lines, angles at 0°, 120°, and 240° form the most efficient way to connect points (the shortest distance). If we're only allowed to use straight lines, these angles allow a way to maximize the area:perimeter ratio of the enclosed 2D shape.

|

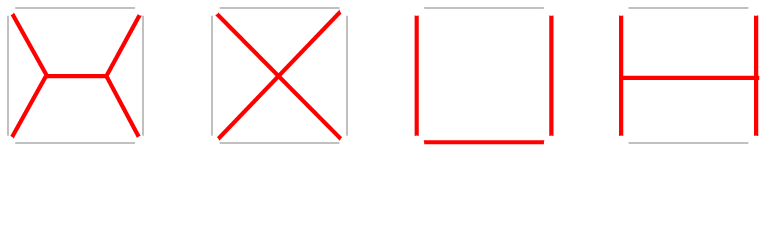

These structures (and graphs) come up often in computer science too, in context to minimum spanning trees, or Steiner Trees* (sometimes also called the 'Motorway Problem'). If you have n towns and wish to build roads (or wire them up with utilities) so that there is a path that connects each of them, when is the minimum length of road (or cable) you can get away with? The answer is a Steiner Tree. All links are straight lines, and if there is a junction between links these all meet at either 0°, 120°, or 240° degrees. There may be more than one solution to a problem, but all solutions will have the same minimum length. |

At school you might have had this demonstrated to you using nails, two parallel sheets and soap bubbles. The bubbles naturally align themselves to reduce the tension in the system (lowest energy state), and this results in the lowest spanning collection of walls. (Most of the time; With soap bubbles, depending the random chaotic things as the bubbles are being formed, it will certainly end up in a local minimum solution, but this might not be the global minimum solution).

*There's a subtle technical difference between a Steiner Tree and a Minimum Spanning tree. In a Steiner tree you are allowed to add intermediate nodes. Theses additional nodes are called 'Steiner Points', and their addition decreases the total overal path length. Implicit from the angle requirement is that every Steiner point has a valency of three.

Square

|

For a unit square, there are two variants of the Steiner Tree. Each of these has a path of length 1+√3 ≈ 2.732 |

c.f. 2√2 ≈ 2.828 which is the path length for two diagonal corners,or 3 units if the points were connected with straight lines and right angles.

Other similar optimisations

If you liked this question, you might be interested in this article about paper condiment containers, or this one about optimal bucket dimensions, or this one about why cans are shaped the way they are.

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.