Wind Turbine Efficiency

There is no question; wind power is going to play an increasingly larger part of society’s energy production needs in the coming years. After setup, it’s a source of cheap, clean, renewable, pollution free energy. (More subtly, it’s also able to produce power without the need of any water; solar also shares these advantages).

Whilst wind speeds are variable, there’s no chance of wind ever running out (as long the Sun keeps shining to warm up the atmosphere, causing pressure changes), and being self-contained, wind turbines can be installed in remote locations, on-site.

Image: Brian McNamara

Image: Brian McNamara

It’s not all goodness; In addition to the variability of winds, there are other challenges. Wind turbines can diminish views, potentially cause noise pollution, and be hazards to flying wildlife.

Some unscientific articles talk about wind power being 100% efficient. That's impossible, as we will see.

In this article, I want to take a high-level look at the theoretical efficiency of wind turbines.

How much energy is it possible to extract from the wind using a turbine?

Basics

Let’s take a basic look at the power of wind. Flowing air has kinetic energy. Power is the rate of energy transfer. How much power is there in blowing wind?

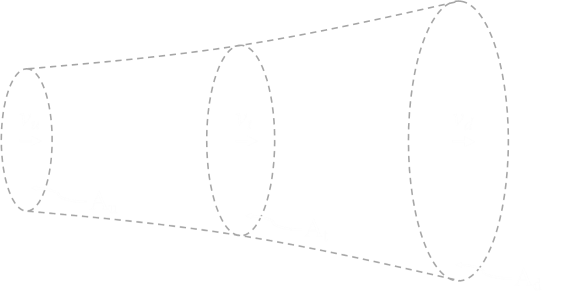

Imagine a cylinder of air; air that could flow through a turbine.

The power available in this fluid (where ρ is the density of the air) is :

We can combine all the constants into one and find that the power availble in a column of wind is proportional to the radius of the cylinder squared, and the velocity cubed.

So, if you're building a windmill, you want to give it as big a swept area as possible. A large windmill, with three times the radius of a small windmill, has potential to generate nine times the power. Similarly, you want to build your windmill in a windy region. Twice the velocity of air increases the power eight fold. Three times velocity is twenty-seven times the power!

Companies may rave about their "low speed" turbine performance, but they are missing the point. Make your windmill as big as you can, and erect it in the windiest place you can find!

Conservation of Energy

|

Energy must be conserved. For power to be extracted by a turbine, energy must be removed from the air. This has consequences. The flowing input air has kinetic energy. If energy is removed, the kinetic energy of the air is reduced, and thus the velocity of the air will also reduce. As the turbine extracts energy from the flowing wind, it slows the wind down. Wind downstream of the turbine will be flowing slower than that upstream. The more energy extracted from the wind, the slower it gets. You can see how this causes a problem; if we were able to extract all the energy from the air it would stop dead after passing through turbine. Where would it go? It would create a blockage so no more air could pass through. Thus, we can see that it's not possible to extract all the kinetic energy from the flowing air. The air has to be given the chance to clear the turbine disk on the downwind side. There is a theoretical maximum for the energy can can be extracted from a flowing fluid, based on conservation of momentum and energy equations. This phenomenon was investigated, independently, by three scientists (whose names will be familiar to all students of aerodynamics and fluid mechanics):

|

|

It's theoretically impossible to extract all the kinetic energy out of the wind with a turbine. |

Actuator Disk Theory

To derive the theortical efficiency, we're going to use actuator disk theory.

I've written about actuator disk theory before, when I looked at which way should you point a fan to cool a room (and how it is possible to blow out a candle, but almost impossible to suck one out!)

There are lots of assumptions we're going to make. We're going to assume a Newtonian fluid; non-compressible and inviscid (having zero friction) - these are fair assumptions if the airspeed is low (low Mach number). We're going to assume no rotation of the fluid (1D flow), and that there is no hub in the turbine so that the velocity across the entire turbine disk is the same (and purely axial). We'll assume the tubine is made of an infinite number of blades (the actuator disk).

Below is a diagram of the stream tube of fluid that passes through the turbine disk. Upstream of the turbine, the air has velocity vu, and the flow has an area Au, at the disk is has vt, At, and downstream vd, Ad. The pressure of the air on the upstream side of the disk is P1 and on the downstream side is P2. The ambient pressure is P0. The pressure difference either side of the actuator disk is how the power is extracted.

Clearly, from a conservation of mass perspective, the product of the area and velocity at at point is the same (we made the assumption that the density remains constant).

As the velocity of the air decreases, the area will increase. The cross sectional area of the streamtube downstream of the turbine will be larger.

Force on the turbine is equal to change in momentum over time, and this is equal to the pressure difference over the disk multiplied by the area. The mass flow rate is ρAuvu, and the Δv is the difference between the upstream and downstream velocities.

From conservation of mass, we know that Auvu = Atvt, and we can substitute this in.

Using Bernoulli we can perform a calculation for conservation of energy for the fluid on both sides of disk (we can't do this across the disk as energy is extracted), and combining these we can derive a second equation for the pressure difference across the disk.

We can combine these two pressure difference equations:

A little rearranging:

This gives our first interesting result: The velocity of the air flowing through the turbine disk is the average of the upstream and downstream velocities.

|

The velocity of the air flowing through the turbine disk is the average of the upstream and downstream velocities. |

If we calculate the power of the air upstream, and subtract the power of air downstream, the difference is the power extracted by the turbine. We know the power is the half the mass flow rate times the velocity squared. And we know the mass flow rate:

We know the velocity through the turbine is the average of upstream and downstream velocities, and rearranging gives this:

We can define Z as the ratio of the downstream velocity to the upstream. Z=vd/vu, to make this easier to manipulate. We now have an equation for the power extracted by the turbine based on the ratio of upstream to downstream velocities.

We're almost there. What we're trying to calculate is the efficiency of the turbine, which is the ratio of power extracted from what is theoretically possible (which is what we stared the article off with). We'll call this efficiency η

Differentiating this with respect to Z and setting this to zero determines the turning points.

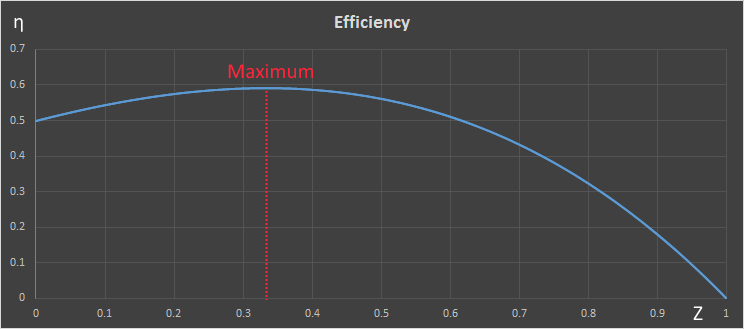

There is only one meaningful root here, and that is when Z=1/3. The second differential is negative, showing this turning point is a maximum. The turbine is most efficient when the downstream velocity is one third of the upstream.

The turbine is most efficient when the downstream velocity is one third of the upstream.

This means the most power can be extracted from the wind in this configuration. Here is a graph of the efficiency curve (the x-axis shows the ratio of velocities, the y-axis shows the efficiency):

You can see from the graph when Z=1, the fluid passes straight through, and no energy is extracted.

Theortical Maximum

Substituting the value of Z=1/3 into the efficiency equation gives the result that the theoretical efficiency, at the maximum point is:

This is the Betz's Law. No turbine can extract more than 59.26% of the energy of a fluid.

No turbine can extract more than 59.26% of the energy of a fluid.

More losses

|

The above calculations show the theoretical limit of energy that can be extracted from the wind. In real-life, turbine blades are not perfect, neather are the genarators, or gears, and there are friction losses, and non-uniform flow of fluid around the turbine. Turbines are also designed for optimal performance at a certain range of wind speeds. Real life wind turbines are typically 40-50% efficient. However, focussing on this value is missing the point. We need to look at total lifetime efficiency of a turbine. How much energy does it take to create the turbine, and to maintain it during it's life? Then, how much clean energy does it produce over its lifetime? This is what we should be looking at. |

Snake Oil

Every now and then, someone comes up with a windmill design that claims to shatter the Betz limit. Either they are selling snake-oil and attempting to hoodwink with technobabbly marketing, or they are comparing differnet things. Shrouded and ducted fans fall into this latter category, and the manufacturers are being creative with the 'swept area', using a funnel to force more air through a small area, yet measuring the windspeed outside this area. In these cases, the push back response is "What's the point?", and "What's the overall effective cost?" You can make your windmill bigger and get a certain amount of power, or make it smaller with a large duct/shroud ducting the same amount of air through?

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.