Gerrymandering

|

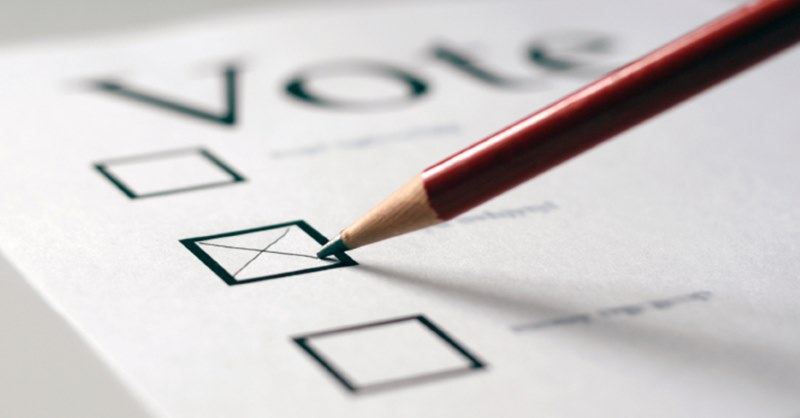

The phrase Gerrymandering is often used by politicians (and political commentators) to describe the practice of moving district boundaries in an attempt to gain more favorable election results. What is Gerrymandering, and how and why can it make a difference? To understand this, we need to learn how voting works. Typically, when it comes to large elections, a country is not voting as one monolithic entity. Instead, a country is tessellated into a multitude of non-overlapping regions (Usually ‘balanced’ so that each region has approximately the same population). By breaking a country down so that each district has the same number of voters it should make the system fair, right? Well, no, it’s not as simple as that. |

|

|

In a traditional election, each territory votes on who they want to be represent them, and the candidate who receives the most number of votes in that territory (the majority) is declared a winner. The results of all the territories are then collated, and an overall party winner is declared (being the party that controls the most regions). That seems reasonably fair, so why does it matter where the district boundaries are drawn if each region contains the same number of voters? It matters because there can be different concentrations of voters across a country and, depending on how the boundaries carve these voters apart, the results can be changed. |

|

This happens because, in any region, at most, 50% of the vote is all that is needed to secure that district. If you have excess votes over 50%, these extra votes are ‘wasted’. If you were able to move the districts’ boundaries to transfer some of these excess voters (voters loyal to your cause) to a different region, you might be able to add sufficient presence to win this second district without impacting the ‘sure thing’ majority from the first region. |

|

Example

To demonstrate this, I’m going to invent the fictitious country of Squaresilvania.

Squaresilvania has 100 registered voters, and two political parties: The Red Party and The Blue Party. Every four years, general elections are held and citizens vote to elect a Minster for their district. A candidate who receives the most votes in their district is declared the winner. The party who has the most elected Ministers selects one of these Ministers to be the Prime Minister.

To make it ‘fair’, the country is divided into ten contiguous territories, each containing ten voters.

Herein lies the problem. Depending on how the county is divided it’s possible to greatly modify which party has the most Ministers, and thus who is the Prime Minister. As we will see, we can influence the entire election depending on how the boundaries are drawn.

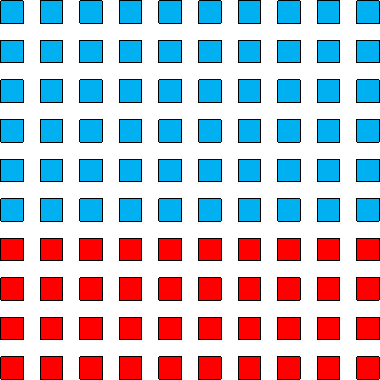

Let’s imagine that, before the upcoming election, a poll has been taken. This poll has found out that 60% of the Squaresilvanian citizens are going to vote for The Blue Party, and 40% of them are going to vote for the The Red Party. At first glance it seems a very depressing situation for The Red Party.

Imagine the distribution of voters is like this (slightly contrived, but it makes things easy to see at glance).

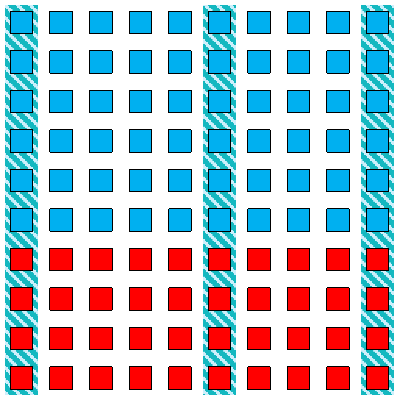

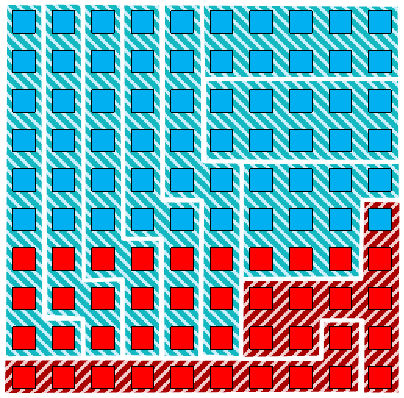

Now, if Squaresilvania were divided into ten equal territories as vertical strips (three examples shown below), then The Blue Party would win every single territory. Each region contains six people who vote Blue and four people who vote Red. The majority wins in each territory and so Blue would win with a land slide. You can understand how Red might feel cheated.

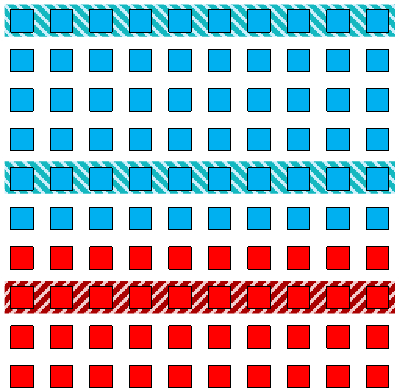

Imagine, instead, if the country were divided using horizontal strips (shown in the diagram below). Here each region is exclusively loyal to one party. Blue wins six regions, and Red wins four. This is a little better for Red (and at least this result mirrors the popular vote in that the ratio of Ministers is the same as the ratio of the total voters), but can The Red Party do better?

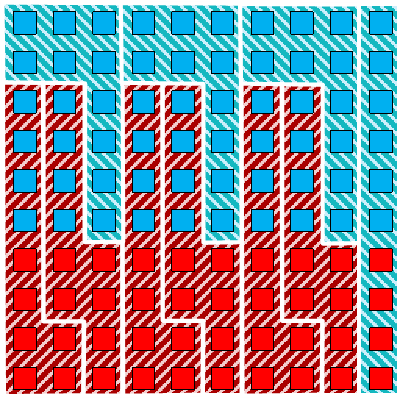

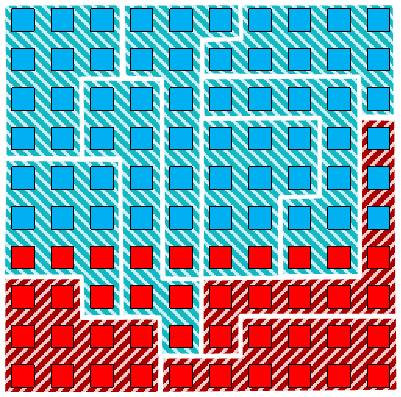

Well, yes they can. If they were able to Gerrymander the district boundaries to their preferences (and trusted the polls about the distribution and location of how the voters were going to vote), they could engineer things something like this below:

In this example, careful boundaries have been selected to allow The Red Party, to not only win more ministerial seats, but also secure the majority of territories (six) so that the can also select the Prime Minister.

How was this achieved? In this topology, Red has chosen the battles to fight. If it’s clear that Blue will win a territory, it’s pointless trying to even put up any fight. Where possible the boundaries have been selected to carve away all Red from the ‘sure thing’ Blue territories.

Similarly, once a region has been formed that has six Red voters it is pointless adding any more Red to that region; any more than six Red votes in a region are just wasted and they could be better leveraged elsewhere.

Between the two extremes of zero and six Red victories, it’s possible to engineer the boundaries to make any number of intermediate triumphs for The Red Party. Here are two more examples where Red wins two and three regions respectively:

|

|

Etymology

|

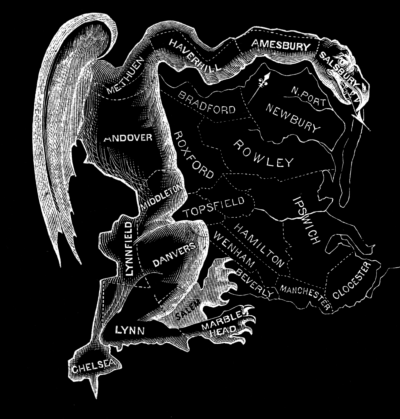

The term Gerrymander was used for the first time in the Boston Gazette on 26 March 1812. The word was created in reaction to a redrawing of Massachusetts state senate election districts under Governor Elbridge Gerry. Governor Gerry had signed a bill that redistricted Massachusetts to benefit his Democratic-Republican Party. When mapped, one of the contorted districts in the Boston area was said to resemble the shape of a salamander Gerrymander is a portmanteau of the Governor's name and the word salamander. The redistricting was a success. The redistricted State Senate remained firmly in Democratic-Republican hands |

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.