Reel to Reel Tapes

If you’ve watched any movies or documentaries about computers in the 1960s, you’ve probably seen computer rooms full of rows of cabinets, all containing front facing reel-to-reel tape storage devices (and flashing lights). They still look cool today.

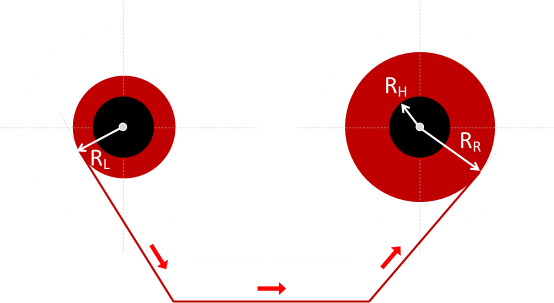

If you watch closely, you’ll notice that, most of the time, the pairs of reels are spinning with different angular velocities. Why is this?

Different Radii

The answer, of course, is that the tape is coming off each reel with a different radius. Depending on the spool diameter, the amount of tape on each side, and the current circumference of the outermost layer of tape, the angular speed needed to get the same linear speed of tape through the reader head changes.

Magnetic tape is (essentially) inflexible, and to get to constant linear speed of tape through the reader head, the supply reel (sometimes called the feed reel), and the take up reel need to spin with constantly varying (and different) angular rates. We’ll investigate, shortly, the mathematical relationship.

History

First a little history. Reel-to-reel format started out as some of the first audio recording and playback mediums (in fact it’s still in use today, though increasingly being displaced by digital and solid state) before being used in computers.

Tape speeds varied depending on quality needed (the faster the speed, the higher the frequency response, the lower the hiss, and the lower the dropout). At the top end, these speeds were 30 inches/sec (IPS), through to 15 IPS in professional recording studios. 71/2 IPS was the highest domestic speed, 33/4 IPS being more common, and 17/8 IPS being used for long duration (typically speech) recording and playback. (For logging purposes, an even slower speed of 15/16 IPS was used where quantity was needed over quality).

Tape storage devices used for computers could obtain speeds much higher, in excess of 100 IPS (around 3 m/s!). The spinning reels had a lot of inertia and there was need to stop, start, and reverse their directions quickly. To allow this (and so that tape did not snap), many feet of loose tape was played out on each side of the read/write head between the reels and this drooped down acting like a buffer (these hanging columns of tape were sucked down and stabilized with suction fans, and were called vacuum columns. The requirement for these tall vacuum columns is the reason why, in the images above, you needed the tall cabinets to house the tape drives. With these long loops protecting the tape, it could be stopped almost instantaneously in the read head, whilst the floating loop was devoured by the slowing down reel that simply had too much inertia to instantly change speed. Mechanical sympathy! They really were incredible pieces of engineering.

Tape

|

The tape used used for domestic purposes was a standard ¼ inch width, and this was stored on hollow reels (imagine two cartwheels glued on either side of a narrow hub) with a typical dimeter of 7 inches. Tape is manufactured as a long narrow strip of plastic onto which is bonded a thin coating of ‘oxide’, typically ferric Fe203 or Fe304, (though sometimes Chromium Dioxide Cr02, or even metal powder). Information is encoded into the tape using an electromagnet and is stored as variations of magnetic flux in the ferromagnetic layer. The process is reversed to read the tape. |

Constant linear speed of the tape through the read/write heads is achieved using a capstan and rubber pinch roller (downstream of the heads to maintain tension on the tape). The supply reel free wheels, but the take-up reel keeps trying to pull the tape through faster than the capstan can supply it (to keep tension and make sure there is no slack). To stop damage to the tape, there is a clutch mechanism that permits the take-up reel the slip it needs.

The thickness of the tape dictated the play capacity of the reels. Early tapes were over 40 µm thick, but over time, thinner tapes were manufactured. "Double Play" tapes were common, which were 35 µm thick, and some as thin as 25 µm were made, but these were very fragile (especially when wound on larger diameter spools, particularly during rewind operations).

With these thin tape thickness's, up to 2,400 feet of tape could be wound onto a 7" spool, giving approx two hours of playback at 33/4 speed.

Growing up, we had a reel-reel tape deck in our house. I remember it being a Tandberg device, with a cool magic-ribbon like recording VU meter.

Math

It's tempting to think about dusting off a little calculus to work out the relative angular rotations of the spools but, actually, there's a simple geometric way to work out the relationship.

We'll also use the principle of conservation of mass! If we ignore the small loop of tape that passes through the read head mechanism (negligible compared to the length of the tape) then, if the tape is not on one reel, it's on the other! (and also, if we unrolled the tape into a long thin strip, it's still the same mass of tape).

We'll also assume that the thickness of the tape in negligible compared to the radius of the spool, and that the tape is incompressible and fits over itself without gaps. In this way, tape on a reel forms a coaxial cylinder of tape.

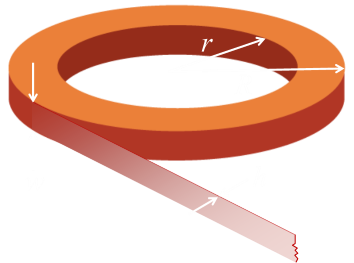

Here's a diagram of a reel of tape. The width of the tape is w, and it's thickness is h. The radius of the inner spool is r, and the outside radius is R.

If we were to unroll the entire tape to make a long strip, we'll define this length to be L.

The volume of the cuboid strip of tape should be the same as the volume as the coaxial pancake of tape.

The width cancels, and simple rearrangement gives an equation for the outer radius of tape R based on the length of tape, and the inner hub radius r.

As the tape is either on one reel, or the other, a chiral version of the same equation, using the complement length, allows that radius to be determined.

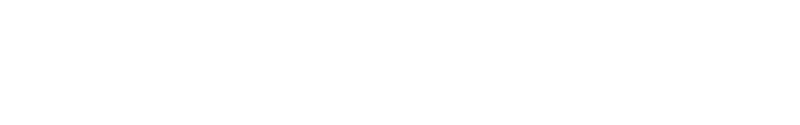

Here is some sample data plotted in graph form. The y-axis shows the Radius of the pancake of tape on a reel (as a percentage of a full reel). In this example, the hub radius is 10% of full tape radius.

The graphs are symmetrical (as we'd expect), crossing over at 50%. It's only at this midway point that the rotation speeds of both spools witll be the same.

Demo

Below is a little applet to demo the speed difference. It's a model of an reel-to-reel tape recorder.

Press the > button to start the player. You can run at 2x speed, and 3x speed using the >> and >>> buttons, and 2x and 3x in reverse using the << and <<< buttons.

The tape counter goes from 0000 (empty pick-up reel) to 9999 (full pick-up reel).

Clicking on the top button between the reels cycles through three 'stylish' spools with either 3, 4, or 5 gaps.

Clicking the 'SHOW' button toggles making the spools invisible to allow the tape to be seen easier.

Finally, the 'RESET' button gives an instant rewind.

Enter the compact cassette

|

In 1962, Philips introduced the Compact Cassette (when I was growing up it was simply referred to as a 'cassette'. Now, also, these devices have been relegated to the pile of obsolete and no longer used technology). Compact Cassettes enclosed two small reels of 1/8" tape in a durable, compact, and portable plastic shell 4"×2.5"×0.5". It's safe to say that cassettes revolutionalized the adoption of popular music (Record players were too cumbersome and fragile to be portable). |

Tape thickness varied from 16 μm, for cassettes that offered 23 minutes of recording per side (the length of a typical vinyl LP record in the day), down to a very thin 9 μm, which offering a couple of hours per side. The transport speed for compact cassettes was specced at 17/8 IPS, the same as one of the earlier reel-reel rates. If you are interested, you can read more details of the spec here.

Cassettes have little windows on their sides that allow you to gauge how far through the tape you are. Often these have graticules and markings on, though, as we now know, the growth rate of the tape pancake is not linear; they are only rough guides.

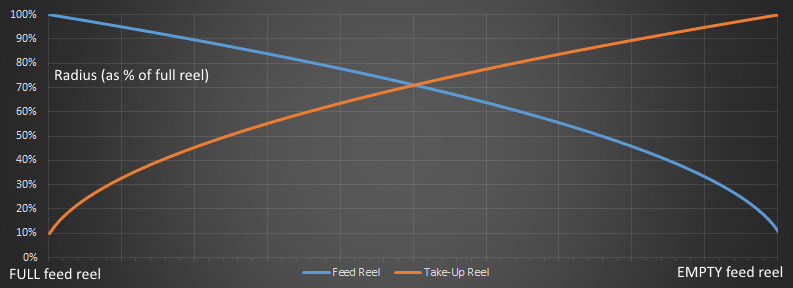

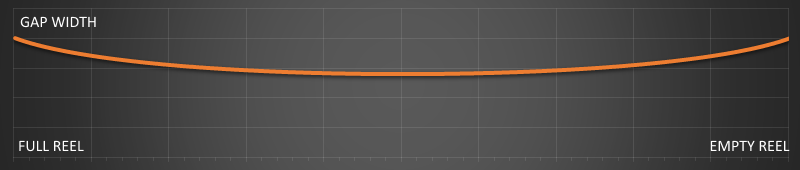

Interestingly, because of how the spools change size, the gap between the two reels is not constant. As the tape plays from one end to another, the gap decreases, to a minimum at the halfway point, then symmetrically increases again.

Toilet Paper

|

Everything that is dispensed from rolls experiences the same non-linear relationship between the radius and linear consumption, including toilet paper, kitchen roll, duct-tape, and paper towels. The closer you get to the center, the faster it seems to get consumed. Miss-quoting Hemingway from The Sun Also Rises (when Mike is being asked about how he went bankrupt) "Gradually then suddenly". |

"Gradually then suddenly"

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.