Piano Keyboards

|

If you play the piano (or enter a lot of trivia quiz shows), you will know that a regular piano keyboard has 88 keys* (52 of these keys are white, and 36 are black). These 88 keys cover seven octaves, plus a minor third. |

|

*Or 89 keys, if you include the key that locks the lid!Thank you, I’m here all week. Try the veal :) |

|

Manufacturers have slightly different implementations, but a typical keyboard is a little less than a metre and half wide. Rather than talking about the overall width of the keyboard, the size is more often quoted as the dimension of the Octave Span, and the range on a modern piano is typically 164–165 mm.

Are all keys created equal?

|

It would probably seem like a good idea to make all the white keys on a piano the same width. This would make a great deal of sense for how you would learn to play. |

|

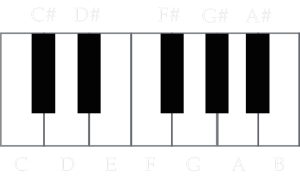

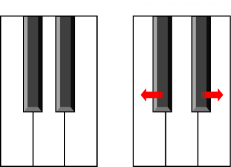

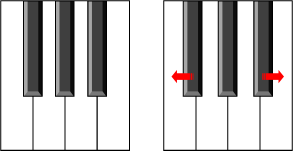

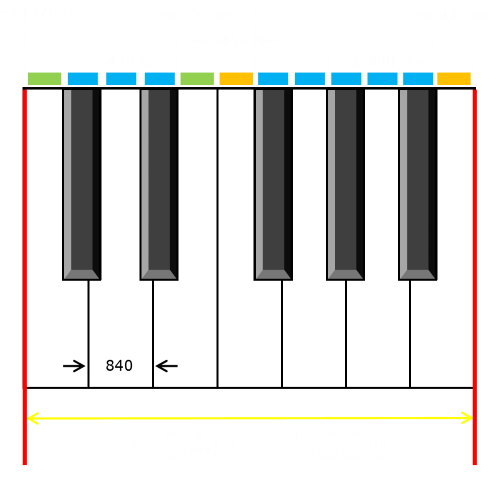

However, a piano has more keys than just white keys. It also hosts black keys (sometimes called accidental keys). In every octave there are 12 notes in the diatonic scale; seven white notes, and five black notes (each a semi-tone apart). The black notes are arranged in groups of two and three. You’re probably familiar with the basic layout. |

|

Image: Terry Madeley Image: Terry Madeley |

This arrangement causes a slight mechanical challenge. Internal to the piano the keys are connected to a series of levers and hammers, and these, in turn, strike a collection of strings stretched tightly over a strong frame. It is the vibration of these strings that causes the musical notes. Ideally, the strings in the frame will be uniformly distributed, but this can’t be possible because of the asymmetry of the distribution of the white and black keys. To simplify the internal mechanisms, it would be nice if all the strings (and the keys) could be spaced so that they are equidistant from each other. To enable this requires that the rear of the keys be equally spaced. Compromises need to be made; how can you make the keys the same width at the back when not all go to the front? |

Compromises

|

The black keys don’t have to be placed so they bisect the white keys. Looking at the diagram on the left (the cluster of keys surrounding the two black keys), it’s possible spread apart the black keys. This allows equal space at for the rear of all these keys. So far so good. |

|

However, when we look at the other cluster of black keys, we see the additional complication of having three black keys. The middle black key needs to bisect the two white keys (for symmetery). If we translate the two outer keys the same amount the same as we did the in the two-key case, the spacing between the outer keys and the center key is different because the middle key does not move. |

|

|

Is there some case that will work for both cases? Is it possible to adjust the spacing so that all the rear edges are equal? Let’s break out a little math and some simultaneous equations. Lets set W as the width of the front of a white keys, and w and b the widths at the rear of the keys. |

|

For the left cluster we get 3W = 3w + 2b. For the right cluster we get 4W = 4w + 3b. We can quickly see that the only way that this can work is if b = 0!— It’s not possible. |

|

So what happens?

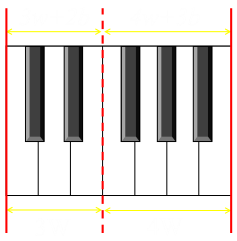

Image: Pedagog Skåne Nordväst Image: Pedagog Skåne Nordväst |

To be honest, I’m no expert here (I’m hoping some of my readers might be able to comment, correct, and educate me), but it seems we want to try and minimize the difference between the narrowest and widest of the rear edges (to give a uniform look and feel), and also aim for a uniform pattern (to simplify the internal mechanisms). Looking at the cheap upright piano we have in our house, I can confirm that the white keys are, indeed, the same width at the front, and the black keys (apart from the G♯) are not centered on the dividing lines between white keys. |

With a litle experimentation, it's possible to see that we can adjust the width of the rear of the keys a little and create a fairly uniform distribution. I'm going to look at two ways. To allow direct comparison, I've normalised the units I'm using. I'm going to consider that an octave span consists of 5,880 units (it was a nice common multiple based on the calculations/scenarios I ran, and divides well by seven and twelve; it has no other significance). Based on what we already know about production keyboards, this means that 1 mm ≈ 35.7 units.

NOTE — For all of these calculations I am not taking into account limits of fit and spacing. In the real world, we need gaps between all the moving parts to ensure they move smoothly, and to allow for play (pun intended) as well as expansion/contraction with heat, humidity, and wear-and-tear. Real pianos clearly have these gaps and spacings designed in; these calculations are to generate the mathematical theoretical spacings before we hand them over to the engineers to finesse them!

Scenario #1

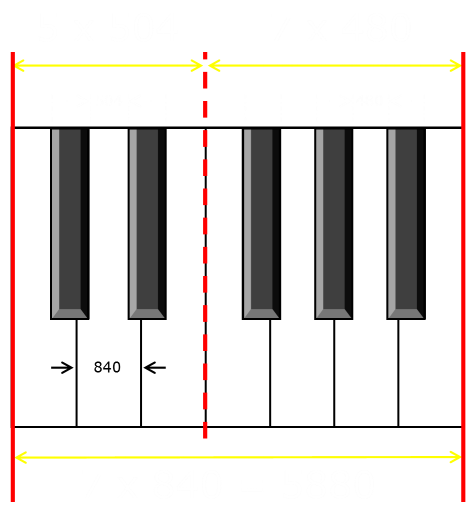

What happens if we treat the left set and right set as distinct batches, and make the spacing at the rear of the keys consistent in their own grouping? Here is the solution based on our normalized units:

This is pretty good. It has the front spacing of the white keys consistent (at 840 units). At the rear there are two distinct widths, 504 and 480 units. The difference between these two rear widths is just 24 units (5%). This is small, and probably not too noticable. It does, however, cause a problem for the engineer who has the design the internal mechanism. The strings on the frame will not be uniformly distributed, and neither will the hammers and pivots. They will grouped in batches of five of one width, then seven of with a shorter width, then five of the wider width … and so on.

Can we do better? Can we come up with as solution that makes the engineer happier?

Scenario #2

I think we can, and to do this we can use the fact that the pick-up for the hammer rod does not have to located directly in the center-line of the rear of each key. As long as it is close the middle of the key (for mechanical empathy), we can translate it side-side a little on each key and distribute the error needed over multiple keys.

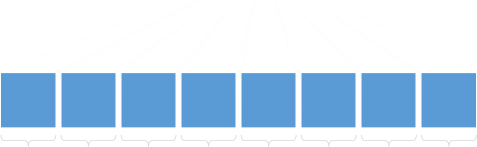

Below is just one example of the compromises that can be made. There are many ways this error can be smoothed out. We'll look at the dimensions first, then see how this might be a better configuration.

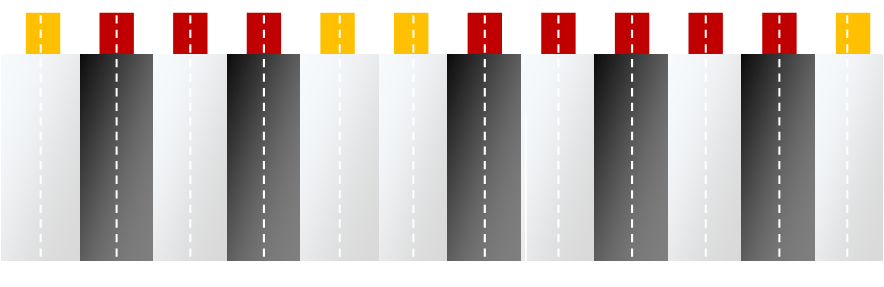

In this design, there are just three distinct widths at the rear of the keys (the front of the keys and the spacing at the front does not change). I've denoted each distinct rear width with a color bar over the top. The rear widths are in the range 455 units to 525 units. This design has symmetery in each group.

The majority of keys are 490 units wide; this is the ideal theoretical width for each key (5,880/12 = 490).

At the end of each run of 490 units are one longer, and one shorter key. The combined width of these is 980 units (490 × 2), so the average width of these keys remains 490 units wide each.

The C and E keys are chiral images (mirror reflections).

The F and B keys are also mirror images.

The G and A keys are mirror images. They may look the same, but the assymetry of the notches on each side means they are not interchangable.

Even though the C and F keys look the same (and are the same width at the front), they have different rear dimensions. They are not interchangable!

The D key is the only white key with a vertical line of symmetry in the distribution of widths over both sets.

|

Why did I select this particular distribution of rear widths? Well, in this particular distribution, the majority of the keys are the correct spacing. An octave is 5,880 units, so with twelve keys, this gives an average rear width of 5,880/12 = 490 units, and most of the keys are the correct spacing. The piano design engineer simply needs to move the pickup lever for the wider key 17½ units off the center of that key, and 17½ units off center the other side for the narrower key and we've solved the problem; Each of the strings can be spaced uniformley! The image on the left shows the inner workings of a piano, and it appears that the hammers and strings are uniformly spaced (not in groups of five of one width and seven of another). This confirms the theory that, even though the ends of the keys are differnet widths, the strings are uniformely distributed by adjusting the pickup locations. |

Final

Here's what it looks like altogether. Below is a rendering to scale.

The colored blocks at the top depict the pickup-locations (an idea of where the levers that are attached to the hammers could be located). These blocks are unifromly spaced. All the strings in a piano can be seperated the same way.

The white dotted line shows the mid-point of each key. For the majority of keys, this corresponds to the same same mid-point of the pickup blocks (these blocks are rendered in dark red). Four white keys in every twelve (C,E,F,B) have the midpoint of the pick-up off-set from the center line of the key. These keys are shown with blocks in orange.

Disclaimer

|

No pianos were harmed in the making of this article. As explained earlier, I have no actual idea how the inner workings of a piano are configured. This article simply describes the way I'd do it if I were designing one. If anyone reading this designs actual piano mechanisms, and I'm way off target, please let me know and I'll write a follow up article. |

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.