Wire Gauges

|

Back when I was a kid in England, I used to dabble with electronics. I’d solder little projects together and wire them up with cables of various thicknesses. The diameters of the hook-up wires I’d use (and the diameter of the solder wire) were measured in units called SWG (Standard Wire Gauge). In what was perverse logic to a child; thin wires were given large SWG numbers, and thicker wires were given smaller SWG numbers. You might have noticed that drill sizes also seem to follow this same inverted standard: Large numbers for small diameter drills, and small numbers for large diameter drills. |

|

|

To the left is a reel of 16 SWG solder. SWG is short for British Standard Wire Gauge, and over the years has gradually fallen out of use for most electronics uses, overtaken by the (more mathematical) AWG, American Wire Gauge. SWG is still used for more niche applications such as jewelery wire gauge and guitar strings. |

Why?

|

Why was the wire scale constructed this way? Why are larger numbers used to describe smaller diameter wires? The answer is related to how wires are made. Wires are fabricated by being drawn (pulled) from large diameter bar stock. Starting with a round rod, this is pulled through a strong die containing a tapered hole of a smaller diameter. As it is pulled through this die, it is plasticly deformed to create a new wire which has a slightly smaller diameter (and also a little longer). |

|

There is a limit to how much the wire can be reduced pulling it through each hole, so if a small diameter wire is needed the rod needs to be pulled through a series of increasingly smaller, and smaller diameter dies. The number of dies that the orginal stock is pulled through is a measure of the gauge. The higher the gauge, the more dies it has passed through, and thus, the smaller its diameter. |

|

The origin for the specification of the 'Gauge' of a wire is the number of dies that it has been pulled through - the higher the gauge, the more times it has been drawn.

AWG

The (British) SWG, whilst a standard, was not quite linear in scale. As mentioned above, there is an alternate standard AWG (American Wire Gauge), and this follows a, much more pleasing, mathematical progression.

|

To the left is a table showing the diameter of wires using the two standards, measured in diameters in inches. You can see that, to a first order approximation, they follow the same order of magnitude. However the older SWG format has some historic values that don't follow a geometric or linear progression.

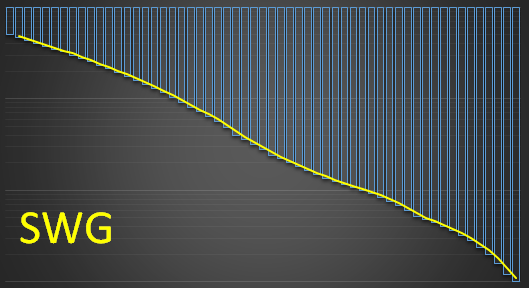

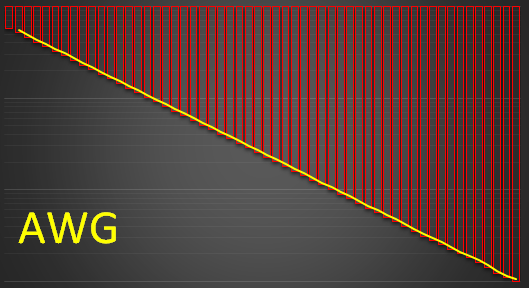

This can be seen clearer if we plot the diameters on a graph. Below are graphs of the two standard (plotted on logarithmic scale because we're dealing with ratios).

The top graph shows SWG, the bottom graph shows AWG.

Notice that the the AWG graph is a straight line? There is a constant ratio between two adjacent wire sizes. |

Ratios

As can be seen, in AWG, there is a constant ratio between each adjacent diameters. What is this ratio? Well, it may surprise you to learn that this ratio is:

Wait, what? Why such a bizarre number? (Inspiration for this posting came from this excellent article.)

Below is a depiction of a collection of wires of various gauges showing a constant ratio of diameters:

By definition AWG 0000 has a diameter of 0.46000 inches.

By definition AWG 36 has a diameter of 0.00500 inches.

There are 39 steps between AWG 0000 (4/0) and AWG 36.

This ratio is approximately 1.123 (inverted it means that each smaller wire is approximately 89.1% the size of it's neigboring sibling).

Other places where similar ratios occur

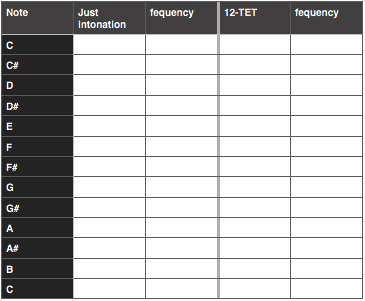

At the risk of enraging half of the internet and waking up vitriolic giants, a similar principle is used in tuning a modern piano. In music, an octave jump occurs each time the frequency of a note is doubled, and in the diatonic scale, this is split into twelve notes. Creating an equal gap between each adjacent note results in each note varying from its neighbor by the ratio 12√2

An instrument tuned this way is said to be tuned in equal temperament. It allows a piece of music to be transposed up and down the scale any number of semi-tones, and sound similar. A fine trait. Pianos are typically tuned this way.

However, 12√2 is irrational, and the frequencies for intermediate notes that this mathematics suggests don’t correspond to the fundamental frequencies (harmonics) that are found from integer multiples of the fundamental note frequency. There’s a measureable difference. Instruments tuned based on the principle of harmonics are said to be tuned with just temperament. If you tuned an instrument by ear (and you had a good ear), you would probably tune it this way. It’s just sounds more ‘natural’, and on a string instrument, after tuning one string, you can use this to tune the next one down.

The differences are small, and individually, when a note is played on its own, I challenge anyone to distinguish between them. However, as soon as notes are combined into chords, the difference is startling.

As an example of this difference, a note midway between an octave pair, in just temperament would have a frequency of 1.5x the low note. However, (12√2)7 is approx 1.498x. This is close, but a fraction of a percent difference.

Chords played in just temperament sound clean and pure and have a very characteristic simplicity.

Chords played in equal temperament have overtones and higher frequency beating which makes them sound more complex.

|

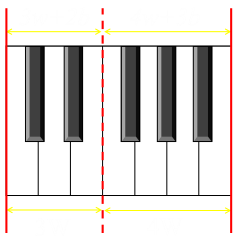

I’m not going to even enter into the debate about which is ‘better’, that’s a pointless exercise and there are pros and cons to each system (and there are also other tuning scheme compromises … the deeper you dig the more you’ll learn, and typically the stronger in opinion people tend to get when describing their preferences). Instead I’ll distract you with another compromise about a piano, and that is an article to I wrote describing how to decide what spacing the black and white keys on a piano should have. |

You can find a complete list of all the articles here. Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.

Click here to receive email alerts on new articles.