Drones and Helicopters

Why are we trying to scale-up drones?

I know this is going to be a controversial post, but I feel I need to make it in respect to engineering and physics. Scaling up a drone is crazy!

What is it with the obsession of trying to scale up drones into passenger carrying vehicles? It just doesn’t make practical sense. Even large organizations (some of whom should know better) are getting in on the act. Sure, it’s a good piece of a PR, and makes for impressive demos and talking points, but from a scientific perspective, it’s the wrong direction. Giant multi-copters are, mathematically, not efficient.

(The only exception to this obsession are the cool, mad-science, Mythbuster-esque home brew projects! How can you see something like this and not smile inside? If you’ve attached a lawn chair to a geometric arrangement of electric motors that are bolted to some aluminium scaffold poles, you have my deference. In my youth, I built a jet engine out of a diesel truck turbo-charger; I know how it goes. Respect!)

Advertisement:

Small Drones

Small drones (multi-copters), are pretty common these days. Their design is totally appropriate for their size. A small modern drone typically has four, fixed-pitch, propellers which are electrically driven. Using a gyroscope, and control circuitry, the craft can be dynamically balanced by a computer making subtle tweaks to the speed of each rotor’s motor. There’s very little mechanical complexity and this works fine. Totally appropriate technology. So far so good.

Medium Sized Drones

As drones increase in mass, things don’t scale well. Bigger propellers are needed to provide the additional required thrust. Because these larger props are heavier, and larger in diameter, they have considerably more rotational inertia. As the props are fixed pitch, the only way to control their thrust (to balance the craft) is to tweak their speed. With the increase in inertia, it becomes harder and harder to finely control their speeds (Once something that large is spinning fast, it really wants to keep spinning at that same speed). It soon becomes impossible to achieve sufficient fine control, without which there can be no stability; there is a limit to the propeller size a drone can use.

The result is that larger drones scale up by increasing the number of motors, rather than increasing the diameter of the propellers. I'm sure you've seen hex-copters with six fans, and octo-copters, with eight. If they need even more thurst, they double them up-down for twice as many! This is madness, and very inefficient. When was the last time you saw a 737 with a dozen engines?

Eight propellers require eight motors. From a pure weight perspective, this is inefficient. One large motor will weigh far less than the combined weight of eight smaller motors. For a medium sized drone you can see the need for multiple rotors to provide stability, but as things get bigger, the problem gets worse.

Aerodynamic Efficiency

Aerodynamically, it's also not a good idea to have multiple disks. It's far more efficient to have one large disk accelerating the air required a small amount, than having multiple smaller disks having to accelerate air faster. It’s this reason that helicopters are efficient at hovering, and jump-jets are not. Both the helicopter and the jump-jet push air of the required momentum to balance their weight. The helicopter does this by taking very large mass of air and accelerating it just enough to give it the required momentum. The jet does this by taking a small mass of air and accelerating it to very high speeds. Once the air has done its job lifting the jet, any additional energy it has is wasted. The jump-jet has given the air excess kinetic energy, and this is not useful. Ideally, you want to give the air the as small a change in velocity as you can get away with.

(For more background on this, read this article about Actuator Disk Theory). You've probably also noticed that electric wind farms like to make their windmills as large as possible rather than utilizing lots of little windmills, for the same reason.

Structural Efficiency

Then there is the additional structural mass needed for the booms to support multiple motors; these motor masses are also cantilevered out a distance away from the center of mass (the outer motors having quite a large moment arm). Also, circular disks don't tessellate, so to get the same swept area as a single disk, the support structure needs to be even larger. Any vehicle made this way will be heavier, have less range, and be less efficient.

Helicopters

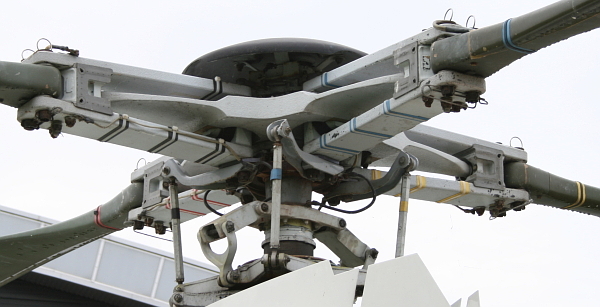

The reason that small drones are designed as they are, and not as small helicopters, is more to do with mechanical complexity. A single rotor helicopter has to use the main disk for lift, stability, and maneuvering. It does these tasks by adjusting the pitch of the blades as they rotate around. Collective pitch is added to all blades, and provides a way to vary overall thrust (pitch is the angle the blade makes with the air it attacks). Cyclic pitch is added to wind up and down additional pitch as the blades rotate around, and this provides directional control.

Image: Helistart.com

Image: Helistart.comFor these reasons, the central hub of a helicopter is a complex system of links, plates, hinges and bearings, and this allows these pitches to be applied as the main rotor is powered. Whilst this, theoretically, can be scaled down (there are model radio-controlled helicopters), it’s overly complex and, as we have seen above, for small scale devices, four simple controlled fixed-pitch propellers do an admirable job.

Helicopters are aerodynamically efficient. They use one disk*, and have a single central powered shaft. The complex mechanics required for a hub is why small drones use simple fixed pitch fans, but, once you've gone above a couple of Kg of mass, a single hub is better.

*Unless they get really, really large and have tip speed limits, or material limits, when sometimes they have two.

In the interests of fairness, I have to confess that a vanilla helicopter, with a single disk, needs a tail rotor for directional stability (the main rotor turns one direction, and the tail rotor stops the craft spinning the opposite way!). This tail rotor reduces the efficiency, as approximately 10-15% of the main power is needed to drive the tail rotor. However, this loss is smaller than the inefficiencies of multi-copters described above. It can also be addressed by making the main rotor a coaxial contra-rotating pair of disks, as seen on various military helicopters (more of this later).

Redundancy

One of the benefits extolled about multi-copters is redundancy and safety. If one of the motors fails on your N-engined drone, you still have N-1 engines that can help pick up the load. In theory, this it true (providing the remaining motors have sufficient headroom to take up this load). With a single engine helicopter you don’t have this redundancy. However, on engine failure, the single massive disk of the helicopter is an asset. If there is an engine failure, the collective pitch can be reduced, and the craft will descend; the upflow of air causes the disk to spin, storing kinetic energy. Close to the ground, this stored kinetic energy can be traded, through pulling up the cyclic, to allow a safe landing. This is called autorotation, and is practiced by all helicopter pilots.

Ducted Fans

It’s possible to increase the efficiency of a fan by placing it in a shroud, or duct. This reduces the air bleeding around the edge of the blades from the high pressure region to the low pressure region. I’ve seen some crazy designs for human scale multi-copters using ducted fans to make them more ‘efficient’.

There are numerous problems with these designs. The first is the additional weight required for the ductwork. The second is, to make a measurable difference in efficiency, tolerances need to be really tight (a very small gap between the tip of the blade and the duct). This requires additional structure (weight) in the shroud to make sure it does not distort. Then there is the need to make the blades very stiff to stop them deflecting and ‘catching’ the shroud (have you seen how much helicopter blades flex, and bend, in gusts?), and then there are real concerns about foreign object ingestion; the gap is so small that it can be fowled, dangerously, by very small objects.

However, the biggest issue is that ducts only work in one direction; that with the flow of air axially through the disk (so they only help going up and down). As soon as the drone needs to translate sideways, the shroud masks and impedes the flow, not only causing massive reduction in lift, but potentially catastrophic loss if parts of the blades stall (something that jet aircraft need to worry about when making landings in extreme cross-wind conditions. With low forward airspeed, and a strong cross-wind component, the angle the air approaches the engine inlet around the nacelle can be extreme).

A potential solution to this problem is to allow the ducts to be steered (tilted) into the direction of flight (vectoring the thrust), but then you have all the complexity of the tilt mechanism (and on each rotor), so why not simply go back to the single disk helicopter design and cyclically adjust the pitch?

Offsetting lift

Small drones are good at hovering (many are used, primarily, as camera platforms.) They start off from one location, go up, move around a little, then come back down to the same location. The majority of power consumed goes into providing the thrust to offset the weight, with only a small part being used to translate the craft.

If we’re building drones to transport cargo (or people), they’ll want to go from point A to point B (not simple up and down!). This means that they’ll need to move horizontally, and this requires propulsion and some kind of lateral thrust. Once forward speed is attained, if the craft had wing surfaces, these could provide lift, offsetting the load provided by the lift propellers. The larger the wings, the more lift that could be generated, and the more efficiently the payload could be moved from one location to another.

Cargo carrying drones should probably have stub wings.

Easier to fly?

Drones are easy to fly because a computer is doing all the juggling required to dynamically balance the system. They are fly by wire in the strictest terms. In contrast, current helicopters are, notoriously, difficult to learn because of the required hand-coordination, cross-coupling of the controls, and practice required in order to understand how the aircraft reacts to inputs. They are this way because the pilot inputs are directly connected to the control surfaces.

In fly by wire, you tell the machine your intentions, and the computer works out what to do to attain this goal; you are oblivious as to what it did*. In a direct control system, by contrast, you directly manipulate each mechanism to get the machine to behave. If the same amount of effort were placed into computerizing the control system for a single rotor machine as has been placed into multi-copter control laws, they would be just as easy to control.

*If you did attempt to control a multi-copter by directly trying to micro-manage the torques on each motor you’d probably have a very short and unpleasant flight.

Range and Duration

All of the inefficiency issues compound. If someone were crazy enough to build a scaled-up multi-copter designed to carry a person, even using an extrapolation for improvement in battery technology, it’s not going to have a duration much more than a current drone (a time measured in minutes), and a maximum range of two dozen miles. Compare this to a lightweight helicopter which has a range of a 200-300 miles, and a duration of up to a couple of hours.

Drone Delivery

There’s a lot of hype in the media about using drones for deliveries from companies like Amazon. Again, it’s a great PR story to grab headlines, but for most things, it’s just not the correct technology. Sure, for urgent medication, or lightweight things, there might be a niche market for aerial drone delivery, but why the hell would you use a flying drone to deliver 50 pounds of cat litter, a new food processor, and two gallons of bleach? It would be quite scary to think of these things flying through the air at 60 mph, when they can be trundled safely, and efficiently, down the road in an autonomous delivery pod?

Crystal Ball

So what will a future human-scale flying craft look like? If we listen to physics, it will not be a multi-copter with a constellation of a couple of dozen fixed pitched fans on a support scaffold. It will also probably not be a vehicle with four or more tilting ducted fans (why go to all the complexity and tolerance concerns, when you can be more efficient with a single rotor, a single motor, and only need one control mechanism?)

It will most likely look something like a conventional helicopter. To remove the need for a stabilizing (power sapping) anti-torque tail rotor, the best configuration would be a coaxial stacked pair of contra-rotating disks (a scaled down version of the image below?). If range is more important than hang-time, they will probably sport stubby little wings to offload the disks.

Prototype SB-1 Defiant, Boeing-Sikorsky. Image Credit: Rotor and Wing International

Prototype SB-1 Defiant, Boeing-Sikorsky. Image Credit: Rotor and Wing InternationalI can also see the possibility of a hybrid design; a device that uses a single, central, main rotor to provide the lion’s share of the lift (with a simplified control mechanism that just provides variable pitch; pure collective), surrounded by a small number of fixed pitch control propellers that control like a conventional multi-copter. The main ‘lift’ engine would provide vertical thrust to handle 80-90% of the weight, with the balance being taken by the smaller control rotors, each exercising fine control to balance, stabilize, and steer (possibly these would each be tilted outwards a few degrees from vertical to provide a horizontal component of thrust, as needed, to translate the craft). In the event of a main engine failure the main rotor blades would have sufficient inertia to allow for a safe autorotation rejection.

The efficiency of the larger rotor would allow a sensible payload, range, and useful on-station time.